There’s something about a boxing match being sold as an ethnic clash that has moved tickets since there were even tickets to move. Call it primal, or even tribal, get philosophical, but at the end of the day, it’s transforming a one-on-one argument into an “us vs. them” scenario, and it just feels inherently normal at times.

Boxing does indeed have the “city vs. city” or even inter-city rivalry working from time to time, though more prevalent — and simpler — are rivalries or match ups between countries.

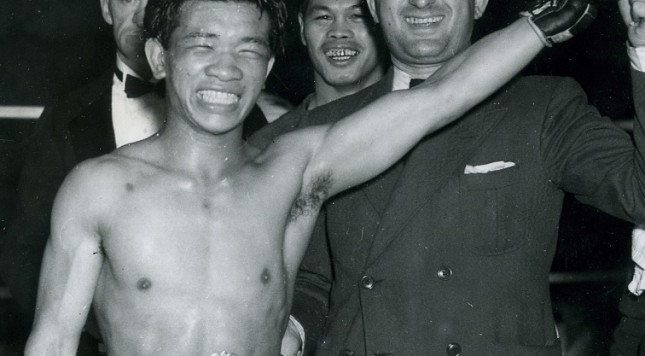

As Manny Pacquiao vs. Chris Algieri inches closer to becoming a reality, we’re reminded that some of the greatest fighters the Philippines had to offer (including Small Montana, pictured; via) actually matched up with some of the greatest fighters of Italian or Italian-American background.

In no particular order…

Flash Elorde UD15 Johnny Bizzarro, 2/16/1963

Elorde, who was already a national hero in the Philippines, was made a 6-to-5 favorite the week of the fight, said the UPI, but the AP reported that Elorde was a “heavy favorite” as the local. By the day of the fight, though, odds had stretched to 2-to-1 for the champion Elorde. Bizzarro’s promoter and adviser was Don Elbaum, also out of Erie, Pa. Before the fight, Elbaum said of his fighter, “Johnny is ready. Though he has never gone 15 rounds he is one of the best conditioned fighters in boxing.”

According to Elbaum, it took Elorde seven tries to finally make weight, and when he reportedly did, Elbaum claimed the scale’s number was still climbing.

An AP reporter wrote from ringside, “Bizzarro, who bled from the nose and from a cut near the left eye during many of the late rounds, kept a persistent attack that caused the veteran Elorde considerable difficulty. The decision was unanimous and by a good margin on the cards of both judges and the referee. … A huge crowd of 40,000 crammed the outdoor Rizal Stadium to cheer for Elorde, a national hero. Italian-born Bizzarro, the underdog, could not match Elorde’s punching power, but he took the Filipino’s best punches and came on to finish in strong fashion. Bizzarro was the aggressor, but the counter-punching Elorde parried his charges with short rights to the midsection and sharp left hooks to the head. Bizzarro was warned several times for butting, and was deducted in the fifth round for that reason. After Elorde had piled up a points margin, he appeared to be content to coast on it, and Bizzarro was the clear winner of the last couple of rounds.”

Famed general Douglas MacArthur allowed the promoters to award the winner with a special trophy in his name, which Villa was presented with, in addition to a belt from Ring Magazine founder and editor Nat Fleischer.

Two days after the fight, Elbaum wrote a protest to the Phillipine Game and Amusement Board, saying, “In my 17 years in boxing I have never seen nor heard of anything so disgusting as what your commission showed in regards toi allowing Flash Elorde to weigh in over the weight for his championship fight with Johnny Bizzarro. At my count Elorde stepped on the scale seven times and never once made the required weight of 130 pounds.” The Board’s response came a few days later, calling Elbaum’s accusations “unfounded and unwarranted.” Their spokesman called the letter “nothing more than a nuisance protest.”

Young Corbett III PTS10 Ceferino Garcia, 10/25/1932

This bout was originally scheduled for September 28, but Fresno news reported that Corbett had blistered his foot in training, and that would postpone the fight into October. It was speculated by other media in Seattle and San Francisco, though, that Garcia’s second KO loss to Freddie Steele killed the potential deal. Whichever was the case, Corbett and his manager Larry White likely used the loss to Steele against Garcia in redirecting the fight to Corbett’s home base, Fresno, Calif.

A UPI report from ringside read, “Young Corbett, III, challenger of the welterweight crown of Jackie Fields, hammered out a 10-round decision over Ceferino Garcia, slugging Los Angeles Filipino, here last night, although he took punishment doing it. Corbett took six rounds; Garcia three and one was even. He led the attack throughout the fight, stinging in rights and lefts to the Filipino’s head and body. Garcia nearly won the battle in the eighth round, when he bored in with an attack to the head that had Corbett hanging on desperately at the bell, dazed and unable to shake off the relentlessly hammering Angeleno. In the fourth and sixth cantos, the Filipino put Corbett on the ropes with rights and lefts to the head, despite the Fresnoan’s stinging body blows and sharpshooting right. All other rounds, except the first, went to Corbett, who flicked his right to the Filipino’s face and jabbed at his body throughout.”

Garcia, said to be the originator of the “bolo punch,” was if nothing else tough, and hard-hitting with his right hand. When he won the middleweight title from Fred Apostoli by KO7 years later in 1939, it perhaps said about as much about the ability of Corbett, who survived to hand Garcia a loss, twice.

Instead, despite a number of high quality wins, Corbett’s early stoppage, title-shedding loss to Jimmy McLarnin — one link in a chain of welterweight champions unable to defend their title around that time — would garner him about as much fame as his accomplishments.

Little Dado D10 Lou Salica I, 3/1/1939

Riding the wave of Filipino talent that Pancho Villa paved the way for, Dado had already face just about all of the quality opposition at or around bantamweight in the Philippines. Upon hitting the mainland U.S. in 1937, Dado posted wins over respectable Northern California locals like Jackie Jurich and Young Joe Roche, before besting his countryman Small Montana in a bout for an abstract version of the flyweight title. It was time to take on a more experienced contender, and former bantamweight champion Lou Salica’s manager Hymie Caplin answered the call.

Oddsmakers felt Dado would get the nod, opening up at 10-to-8, per the San Francisco Chronicle, before widening to 10-to-6.

Harry B. Smith of the San Francisco Chronicle summed the fight up as follows: “Dado had four of the ten rounds, with four even, and Salica had two. If you took into consideration the cleaner punching and the aggressiveness of the Filipino, he should have had the verdict. The crowd booed the decision heartily and the Filipino contingent set up an awful roar. It was one of the best fights for boys of that weight local fans have seen in a long time. Dado was in fine condition and outboxed his man, eluding Salica’s left hooks to the body. Salica did a lot of countering in the early part of the fight and it was his body punches in the clinches that slowed Dado. That was not unexpected, for Dado was the much lighter boy. There were some furious rallies to keep the crowd of 6000 fans on edge. Dado had the first, second, fourth and eighth. Salica was best in the sixth and seventh. Others were about even. There was betting at ringside at 2 to 1 that Dado would win. The house netted $3595, which was a good turn out for the little men of the ring. I still think Dado is the best flyweight in the ring.”

Both men earned purses of roughly $1,000, and both took home about one-third of that, or less. Dado and Salica went on to fight each other two more times in the span of eight months.

Small Montana PTS10 Midget Wolgast II, 9/16/1935

Montana had markedly less success than the aforementioned Dado, perhaps due to his smaller frame and total lack of punch, but Montana had already won on points from Wolgast two months earlier. Montana wanted Wolgast’s NYSAC flyweight title, though, and Wolgast hadn’t made the flyweight limit in almost two years.

Inspector Don Shields had Wolgast and his promoter Leo Leavitt put up two separate sums of $500 as collateral in case Wolgast either didn’t make weight, or didn’t show up at all. But either as a publicity stunt, or to actually get his weight down, Wolgast hired Benito Mussolini’s personal dietician Giuseppe Consolo to help him make the flyweight limit, as he had weighed in at 123 lbs. just two weeks earlier.

Writer Art Rosenbaum said from ringside, “Ten years after Pancho Villa took his fly weight title to the grave, another Filipino Kewpie doll brought back the 112-pound championship last night. Small Montana, as clever as they come, outboxed Midget Wolgast to earn referee Eddie Burns’ decision after ten rounds at the Oakland Auditorium. It was also in the East Bay ten years ago that the flashy Villa fought slender Jimmy McLarnin, then died two days later following an operation for an abscessed tooth. Last night Montana regained that title in the name of Villa, and even thought Wolgast finished like a true champ, his willingness could not offset the rapid left-hand darts of Montana. In the eighth round the Midget had his left eye cut and during the last three rounds Montana was sharpshooting for that target. Wolgast made his biggest offensive in the seventh round when he slashed with sharp left hooks to the head and sweeping right hands to the body. He landed the hardest punches of the fight in that round, and it appeared that Montana was about to lose his long lead. But the Filipino came back to score in the eighth and ninth and hold the final round even to win an undisputed verdict.”

Montana’s short stature continued to be an issue for him, as he was the smaller man by at least a few pounds in almost all of his losses. He defended the belt only once before Scottish legend Benny Lynch defeated him to unify the flyweight title.

Frankie Genaro SD15 Pancho Villa, 3/1/1923

When the fight was announced for Madison Square Garden in late February, the New Jersey boxing commission had just declared that it had lifted its ban on Genaro for failing to meet Villa in Jersey City following their first fight, which added up to a close newspaper win for Genaro in the same city. Additionally, before the bout, NYSAC Chairman William Muldoon ordered Genaro to be fined $3,000 for not facing Villa in December of the previous year, and declared the fine would have to be paid before he was allowed to legally schedule a bout in the state of New York, never mind scheduling to fight Villa for the American flyweight title.

The expectation, as was widely reported, was that the winner of Genaro-Villa III would face the division’s champion-in-recess, Jimmy Wilde. Promoter Tex Rickard all but guaranteed it, claiming to have a handle on the negotiations of such a clash. A news wire via the Plain Dealer called advance ticket sales “unusually heavy,” and Villa was approximately a 7-to-5 favorite over Genaro by fight time, even though Genaro had already beaten Villa twice.

The Boston Herald said of the fight, “For 10 rounds the bout bordered on sloth, but in the last five the mixing was so furious that the spectators were in almost constant uproar. … The last round probably gave Genaro the title. Twice his right hand caught the Filipino squarely on the point of the jaw and the champion’s knees sagged. But Pancho came back and after clinch was in a furious exchange when the bell rang. … For one of the few times since boxing bouts have been permitted under recent legislation, the crowd became demonstrative to an extent that worried the police, and squads of bluecoats had difficulty in clearing the aisles.”

INS editor Davis Walsh (who would later pen an infamously racist passage about Joe Louis following his 1935 destruction of former champ Primo Carnera) wrote from ringside, “‘One a minute,’ says Henry Ford, speaking in terms of tin economics. ‘One a minute,’ echo the judges of prize fights at Madison Square garden as they make and unmake champions. They unfrocked another title holder last night when Frankie Genaro was given the decision over Pancho Villa after 15 fast rounds and the verdict, which carried with it the American flyweight championship and the privilege of wafting a few at Jimmy Wilde for a suitable percentage of the house, was only semi-popular. In fact it created almost as much of a furor as the decision, rendered less than a week before, whereby Gene Tunney was declared the winner over Harry Greb in a bout for the light heavyweight title. The gentlemen of the press box were divided into two camps over the verdict, some claiming that Villa had won, other contending that Genaro justly earned whatever honors might be gained from a hairline decision.”

Another ringside reporter, Harry Newman, wrote, “Frankie Genaro, sturdy little Greenwich Village Italian, tonight became American flyweight champion. Genaro outboxed, outguessed and outgamed Pancho Villa of Manila for nearly three-quarters of their journey in their fifteen-round bout at Madison Square Garden tonight. Genaro was too smart for the brown boy from the Philippine islands. He made the running in the early rounds, then permitted Pancho to snatch the lead away when half the distance had been traveled. From the sixth to the tenth rounds it looked as though Villa had taken the jump and was not likely to be headed. However, Frankie stayed close at his heels, and when they came into the stretch — in the last five rounds — Genaro stepped out to outbox Pancho and succeeded thoroughly.”

*****

Probably having more say than ethnicity in the outcomes of these matchups were the savvy, skills, speed, power and styles of these men. From plodding bangers, to southpaw cuties without much power, but infinite ability to make a smash up about footwork, they simply came along at a time when such meetings were marketable.

Almost 90 years later, not much has changed, overall. Nationality is still a factor in the promotion and hard sell, but not in the end result. The scoreboard is umpteen to umpteen, but race always helped promoters stack the deck in their favor.