War is always a defeat for humanity, said Pope John Paul II.

Karol Wojtyla, bless his heart, wasn’t a college football fan — if he had been, he would have realized that in at least one case, “war” was a blessing.

It’s true that Steve Spurrier versus Bobby Bowden from 1990 through 2002 was extremely special at Florida and Florida State. It’s obvious that Tom Osborne versus Barry Switzer from 1973 through 1988 was nothing less than magical at Nebraska and Oklahoma.

Darrell Royal-Frank Broyles in Texas-Arkansas in the 1960s and early ’70s.

Ara Parseghian-John McKay in Notre Dame-USC during the same time period.

Bear Bryant-Johnny Vaught in Alabama-Ole Miss from the late 1950s through 1970.

Several great coaching rivalries have existed throughout the decades, and the ones above rose to the top in college football. Yet, no single coaching matchup quite captured the imagination of a nation the way the Ten-Year War managed to do.

*

From 1969 through 1978, the titanic struggle between Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler in the Ohio State-Michigan rivalry captivated college football fans and swept the Midwestern United States into a frenzy.

The Rose Bowl has remained the one bowl game which can stand on its own as an always-special event even if not attached to the BCS championship or (in this new era) the College Football Playoff. In the 1970s — before the explosion of new bowl games in a more bloated lineup — the Rose Bowl’s place atop college football’s postseason pyramid was that much more entrenched. The event’s resonance and centrality were that much more profound.

Why did Woody Versus Bo dominate the national conversation — in the present tense and in the years after the rivalry ended due to Hayes’s unfortunate punch at a Clemson linebacker in the 1978 Gator Bowl? Very simply, either Ohio State or Michigan always found itself in the Rose Bowl for 13 straight seasons.

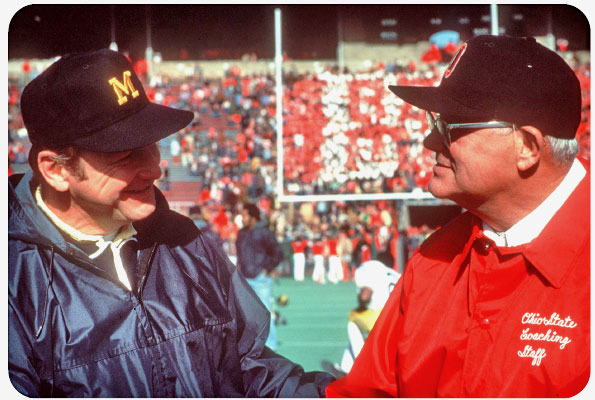

This photo comes from the 1981 Rose Bowl, which gave Bo Schembechler his first win in the Granddaddy at Michigan. (Copyright Joseph Arcure)

From 1968 through 1980, two and only two Big Ten teams made their way to Pasadena. Indiana reached the Granddaddy in the 1967 season, and it wasn’t until Iowa broke through in 1981 that the Ohio State-Michigan stranglehold on the Big Ten was broken. When Woody and Bo met on the gridiron — staring at each other from the opposite sideline — a plane flight to Pasadena hung in the balance. Through the 1974 season, the loser did not go to any bowl game whatsoever, greatly magnifying the importance of every edition of The Game. It wasn’t until the 10-10 tie between the two teams in 1973 — controversially resolved by a Big Ten decision to send Ohio State to Pasadena — that the league gave fresh consideration to the notion that second-place teams or credentialed non-champions should be free to go to other bowl games. Beginning in 1975, the Big Ten opened its doors to other bowls, and while Ohio State made the Rose Bowl, Michigan was able to play in the similarly prestigious Orange Bowl against defending national champion Oklahoma.

Woody and Bo — they were genuine American originals, large personalities fit for the big stage. They dominated their league, and they changed the way the Big Ten did business. Their decade of competition showed that while war is generally not a good word to use in sports, the Ten-Year War (in capital letters) marked a rich period in college football history.

Woody Hayes coached his last Rose Bowl in 1976 against a very young and ascendant Dick Vermeil, who soon left UCLA to bring the Philadelphia Eagles their first Super Bowl appearance a few years later.

*

This leads us to the question everyone in the sport is asking: With Jim Harbaugh coming to Michigan, can college football dare to hope for ten years of games against a sure-fire Hall of Fame coach, Urban Meyer of Ohio State?

If these coaches can last 10 years in Ann Arbor and Columbus, college football fans should be blessed with a series of Michigan-Ohio State games that will be spoken of the way the 1970s were in Big Ten country.

The obvious but necessary point to make about the Ten-Year War is that it was balanced. Michigan and Ohio State both made five Rose Bowl appearances in that span of time. One of college football’s signature rivalries was contested on very even terms.

In the 1990s, Lloyd Carr had John Cooper’s number. In the 2000s, Jim Tressel owned Carr. The last three seasons have been all Ohio State following the Buckeyes’ lost season of 2011. The 2006 edition of The Game — pitting the top two teams in the country against each other, in a 3:30 time slot, with Schembechler dying the day before — achieved an immortal place in the history of the sport, but for the most part, this rivalry has lacked an even-steven Woody-Bo quality ever since Earle Bruce left Columbus in the late 1980s. It’s been a series defined by prolonged periods of dominance on one side or the other, less an annual jousting match that could go either way in every given year.

Harbaugh’s arrival in Michigan could change all that, giving Michigan a man worthy of engaging in a chess match with Meyer, who has lost all of two regular-season games since arriving on the scene in Columbus.

You can debate whether Harbaugh will be lured back to the NFL or not, but it’s fairly safe to say that when comparing these two coaches, the NFL is a flight risk only for Harbaugh and not Meyer, a coach whose life would be so much more consumed if he ever did coach in the pro ranks. Meyer had to re-evaluate his lifestyle when he burned out at Florida, so a jump to the NFL isn’t really worth considering. Burnout represents Meyer’s challenge at Ohio State (which he seems to be managing very successfully right now). The NFL — which Harbaugh didn’t quite conquer in San Francisco (though he came extremely close) — might offer a siren song several years from now, but if Harbaugh has been permanently turned off from the pro game due to the idiocy he witnessed from Jed York and Trent Baalke, he could very easily settle down in Ann Arbor and thirst for a special place in college football history.

Pete Carroll might have left USC just because he wanted to put the NFL at his feet, but it’s hard to deny the notion that impending NCAA sanctions led him to get out of Dodge’s Los Angeles precinct. He might have stayed longer at USC if his situation wasn’t about to become immensely complicated. It’s true that one plot twist here or there could change the outlook for Harbaugh or Meyer — that’s something to keep in mind, but on the back burner, not the front burner.

Even though there are fewer Joe Paternos and Bobby Bowdens today — coaches who decide to plant roots at one program — there are certainly examples of coaches who like being in one place. Mack Brown at Texas and Bob Stoops at Oklahoma remained competitors for a long time until Brown was forced out. (Stoops could find a hot seat if 2015 is as disappointing as 2014 was in Norman.) Nick Saban is very comfortable at Alabama and seems likely to stay there for the rest of his career, however long it lasts. Les Miles isn’t going anywhere at LSU, and he’s already been there a decade.

You’re free to express skepticism about Harbaugh’s long-term commitment to Michigan, but as you just saw:

1) His professed “love for the NFL” didn’t really hold up under scrutiny, contrary to the notions of many NFL reporters and “information men.”

2) If 49er brass was stupid enough to fight him instead of accommodating him at every turn, that’s an easy and logical reason for Harbaugh to want to remain a college coach for the rest of his coaching career.

College football fans are certainly hoping Harbaugh has lost his appetite for the NFL’s bizarre subculture. If that turns out to be the case, we could be in for at least 10 years of blessed, blissful War on the gridirons of the Midwest.