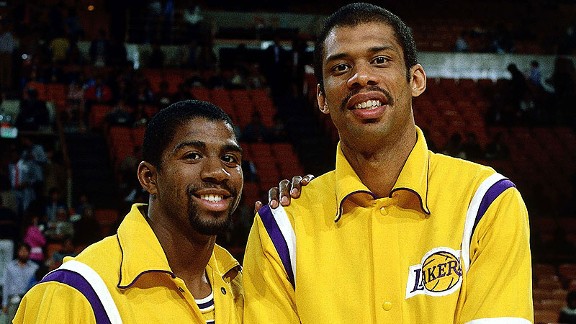

Magic Johnson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, by any account among the 10 to 12 best basketball players who have ever lived, and very likely one of the two best players at their respective positions, will always be remembered most for what they did together.

The point guard in a forward’s body, united with the author of the skyhook, won five championships and exhibited near-total dominance of a whole half of the NBA (the Western Conference) in the 1980s. They transformed the NBA alongside Larry Bird, Kevin McHale, Robert Parish, Julius Erving, Maurice Cheeks, and Andrew Toney. Magic and Kareem — more than any other same-team pair of players — revitalized professional basketball in the United States, setting the table for Michael Jordan and the Dream Team to develop the sport internationally.

Yet, what is fascinating about these two giants of pro basketball is not so much that they did win — and achieve — so much together. It is striking that for all the ways in which they are intimately linked by the course of human events in the NBA, they also fill in each other’s gaps. More than that, they tell the story of professional basketball over a specific period of nearly 25 years, from the late 1960s through the early 1990s. What Magic and Kareem did and said — with their basketball, not their words — in that period reverberates through the modern NBA in ways you might be able to appreciate… but haven’t been consciously aware of.

*

They obviously met as teammates in the preceding months, in the offseason before the 1979-1980 NBA campaign, but this was the first public moment Magic and Kareem shared. It was not fun for Kareem at the time, but in retrospect, it’s a comedy classic. The rookie, in his first regular-season game as a pro, is so caught up in the excitement of his new career, playing with a legend of the game and knowing that everything is possible:

Over a full decade before that play, and roughly 12 years after it, Kareem and then Magic could legitimately be seen as the central authors of the story of the NBA.

Eleven years before October of 1979, the Los Angeles Lakers began their first season with Wilt Chamberlain, the man who — finally united with Jerry West and Elgin Baylor — was supposed to be a transformative figure in Laker history.

While Wilt did win a title on the 1972 team that won 33 games and affirmed a place as one of the best single-season teams ever, a Laker golden age — promised in presence if not in word by Wilt — did not materialize. The Boston Celtics (in 1969) and the New York Knicks (1970 and 1973) stopped the Lakers in the NBA Finals, undercutting the notion that Chamberlain was going to make Los Angeles the dynasty Boston had built in the 1960s.

In 1971, the Milwaukee Bucks were good enough to win the NBA title, behind a giant of the ’60s in late-period form, his peak a few years in the background. That declining titan, Oscar Robertson, was still able to climb the championship mountain and lift his first professional trophy because young Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was able to blend with him so beautifully.

Here’s where the player-evaluation calculus becomes more complicated, though: It’s true that the Bucks did not win another world title (though they took the Celtics to seven games in the 1974 Finals, marking Robertson’s last playoff run and the end of his remarkable career), but Robertson was at the end of the line. It’s not as though the Bucks had any time with prime Kareem and prime Big O.

The Lakers might not have enjoyed the absolute best of Elgin Baylor in 1969 — certainly not the supernova of the early 1960s — but in that 1968-1969 season, they did claim Baylor, West and Wilt as their own. By any reasonable measurement, that should have been the season when a freshly arrived big man paired with an all-time wing (Baylor) and point guard (West) to put the Lakers over the top. That Chamberlain didn’t — despite having many more years left in his career than Bill Russell — certainly dents his legacy and where he lands on the all-time list of great centers. The question for evaluators is simply, “To what degree?”

*

Basketball has always been unique among North American team sports in that anywhere from one to three players frequently become the central focus of a team (and by extension, an organization) to the reduction of the supporting cast.

One can’t quite draw that sharp a line in the other sports, with the possible exception of hockey, in which goaltenders do acquire considerable centrality. Yet, even then, a great goalie with a large quantity of average players isn’t likely to get very far in the Stanley Cup Playoffs.

In football, a quarterback matters a ton, but there are too many positions of importance to say that with only three or four of the right guys, an NFL squad can compete for Super Bowls and make them every now and then. Football teams demand depth, at least with one anchor in each layer of the field: the secondary, the linebackers, the defensive front, the offensive line, the receivers, and the quarterback/running back. If a whole layer of the field lacks one prime player, that team is going to be exposed over the course of a full season, such that championship aspirations are not realistic.

In baseball, two ace-level pitchers can carry a team through the playoffs, but those two aces can’t carry a team through the regular season. The bullpen and the batting order have to have at least three performers of considerable quality if the team is going to get to the playoffs and allow its aces to do the rest.

It’s only in basketball — without hockey’s use of three or four lines; without football’s huge rosters; without baseball’s bullpen and wide array of position players — where a small cluster of athletes, surrounded by merely competent (read: not special, but able to carry out basic tasks) performers, can win championships. Core playoff rotations (not including players limited to under 10 minutes per game) will often not exceed eight players. If teams can pair one great interior performer with one equally imposing perimeter or wing player, they can inject themselves squarely into the pot of title contenders. A third properly-chosen piece — adding to a team’s balance and diversity in the right proportions and the right style — will sometimes put that team over the top, as long as the peripheral role players are able to maintain a certain tolerable standard.

The fact that prime Kareem and old Oscar Robertson won as many titles as the combination of prime Jerry West, late-period Elgin Baylor, and “a-few-years-left” Wilt Chamberlain (one) suggested that as long as Kareem could pair with a prime point guard before he got too old, he’d win big.

After Kareem went from the Bucks to the Lakers in the mid-1970s, he didn’t have that prime point guard — and he didn’t come particularly close to sniffing the NBA Finals — until the fall of 1979.

Then the music began to play, and an inversion of Los Angeles Laker history began.

*

In the late 1960s, Jerry West and Elgin Baylor needed a big man to represent the final piece of the puzzle. West got to taste championship glory in 1972 with Wilt, but Baylor — his career ended by injuries — was not part of the team when the playoffs began and the Finals ended in triumph. He received a ring in a classy gesture from the Laker organization, but he knew — just as well as anyone — that he had not really made the climb as part of a band of brothers.

In 1979, the Lakers — having been adrift for several seasons — were in the position opposite 1968: They needed a backcourt star to pair with a big man this time around. Quality supporting cast members Norm Nixon and Jamaal Wilkes were already in the fold, but without a dynamic perimeter player, Kareem would not have had enough help to bring the Lakers the riches they had hoped for in the late 1960s… and didn’t quite attain.

Enter Magic.

*

Kareem was 32 years old when that 1979-1980 season began. Not even he could have known that he would still be a highly capable player for 10 more years, into his 40s. When Magic arrived, a reasonable position held that the rookie and The Captain had five or six years in which to get something done, a lot like Wilt when he arrived in 1968 with The Logo and Elgin Baylor already in L.A.

Unlike the previous Laker core in the late ’60s, this one gelled immediately. Yet, as much as Magic and Kareem thrived together, the bookends of the Lakers’ best 12-season period were punctuated without the two occupying the court at the same time.

When the Lakers won their first title in the Magic-Kareem era, Abdul-Jabbar did not play in the close-out contest. In Game 6 of the 1980 Finals, Kareem wasn’t in uniform, sidelined by an ankle injury suffered in Game 5. (An underappreciated story from the 1980 Finals is that Kareem gutted out the remainder of that fifth game on adrenaline, giving the Lakers a 3-2 series lead heading to The Spectrum for Game 6.) Magic played center and delivered the game of his life — 42 points, 15 rebounds, 7 assists — as the Lakers promptly showed that they found the perfect complement to a previously existing star. The immediate return on investment is what the franchise expected in the 1968-’69 season, but did not receive. In this sense, Magic and Kareem filled a gap together… only Kareem wasn’t there for the finishing touch.

The other bookend of the Lakers’ greatest era was 1991. Kareem had retired two years earlier, and Pat Riley called it a stay in L.A., preparing for the next chapter of his life in New York with the Knicks. Magic was still there, however, and he willed the Lakers to the Finals.

Was it wishful thinking to have hoped that Kareem could still play at his 1987 level in the 1991 Finals? Sure. That did not change the fact, however, that without an elite big man (the Lakers had to settle for Vlade Divac — good but not special), Los Angeles could not expose the Chicago Bulls at their weakest point. A fellow named Michael Jordan took over, with Scottie Pippen learning from a personally crushing 1990 playoff failure against the Detroit Pistons. The new dynasty in the NBA took the torch from the Lakers in a fitting moment of symbolism.

With Kareem and Riley gone, Magic’s last true run at a title marked, for all intents and purposes, the end of the 1980s Lakers. The Pistons had won two straight titles before the Bulls did, but the reality of the Bulls picking up where the Lakers left off was too rich in power and significance to ignore.

Magic — lifted to a championship height by Kareem during the 1980s — missed his old buddy in that ’91 Finals series. More to the point, though, Magic found himself in the very place Jerry West and Elgin Baylor occupied through the 1967-’68 season, when the absence of a great big man clearly stood out to them as the reason they lost one NBA Finals after another.

Magic and Kareem — they weren’t on the floor in Game 6 of the 1980 Finals, when their run truly started. They weren’t on the floor in the 1991 Finals, Magic’s last close pursuit of a championship. Yet, from the start of their partnership in 1979 through the end of Magic’s last consequential season in 1991, they transformed the Lakers and made the franchise what it is today: a franchise on par with the Boston Celtics.

It was the Kareem-Magic combo which, at long last from a Laker perspective, beat the Celtics in a Finals series. This happened in 1985, after the humiliation and desolation of 1984. It was the Kareem-Magic combo which enabled the Lakers to not only beat the Celtics in a Finals series, but to close down the series in Boston Garden. Kareem and Magic beat Boston again in 1987 to show that 1985 was hardly an aberration. (Think of the St. Louis Hawks beating the Celtics in the 1958 Finals but losing in three other Finals matchups with the C’s.) In 1988, the two Laker greats took the next step in affirming their shared place in basketball lore: They provided the fuel for the first repeat championships since the very team that made the late-’60s Lakers so miserable, the 1968 and 1969 Celtics.

Kareem and Magic won a lot, but as you should be able to see by now, the fact that they won on such a large and consistent scale is only part of the story. What truly unites Kareem and Magic as champions and elites in NBA history is how they flip-flopped the balance of power — and the flow of history — between the Celtics and the Lakers. Everything the Lakers hoped to be but weren’t in the late 1960s, Kareem and Magic became in the 1980s. Everything the Celtics had been for the Lakers in the 1960s, they ceased to be once the 1985 Finals ended.

*

Kareem and Magic shared that 1979 night in San Diego — when the veteran knew this was just game one out of 82, and the rookie treated every game outcome like the NCAA tournament final he had just played against Larry Bird and Indiana State in Salt Lake City, a few months earlier.

They shared a title in their first year together, even though Kareem was not on hand to personally hug Magic in Philadelphia after Game 6 — that was a night which truly deserved the kind of celebration Magic displayed in San Diego, at the start of a long season.

Their repeat title catapulted them into a different stratosphere of basketball immortality, without question.

Yet, the crowning moment of both Magic’s and Kareem’s careers — the moment when they made themselves Lakers on a larger scale of greatness, with more cathartic and healing power than at any point before or after — was that 1985 clincher in Boston Garden.

It’s quite surprising, and more than a little disappointing, to not have a Google image of the moment, but it is — for Laker fans old enough to have seen it on live television — the most richly satisfying scene in franchise history.

At 4:08 in this video, Kareem celebrates with his teammates at the end of Game 6 of the 1985 Finals. When he raises his finger and holds it there for several seconds, it is as though each second represents a Laker loss to the Celtics in a previous NBA Finals. There were eight of them, seven in Los Angeles and one in Minneapolis:

Even if you weren’t a Laker fan on that Sunday afternoon, you had to appreciate how powerful and resonant that moment was — perhaps not on the scale of the Boston Red Sox winning the 2004 World Series after an 86-year drought, and perhaps not on the scale of the New York Rangers winning the Stanley Cup in 1994 after a drought of over half a century, but still an event which rippled through the pages of the past, echoing through the corridors of time.

This was the work of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Magic Johnson.

*

EPILOGUE

The comparative success of the Kareem-Magic tandem, relative to the West-Baylor-Wilt trio, invited one cross-generational Laker comparison. Yet, in many ways, it has spawned more such comparisons in the modern age, the next period of roughly 22 to 25 years which followed the 1969 through 1991 period covered by Kareem’s and Magic’s careers (not including Magic’s brief comeback after contracting HIV).

When they were brought together in the latter half of the 1990s, Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant began their never-boring, not-as-harmonious-as-Magic-and-Kareem relationship. Perhaps because of the friction in that pairing (perhaps also because of emergent internet appetites for round-the-clock gossip, and very probably a good deal of both), the question wasn’t so much, “Would the Lakers win big with Shaq and Kobe?” The main query often was, “Which player is more responsible for the Lakers winning big?” A more individualistic focus emerged, and the way both Shaq and Kobe played — and carried themselves — did nothing to reduce that line of questioning or its intensity.

The other way in which the most recent Laker dynasty differs from the 1980s is that Los Angeles did not face a team remotely close to the 1980s Celtics in any of those first three NBA Finals from 2000 through 2002. Even the 2004 Detroit Pistons weren’t in the same league as the great Celtic teams of the Bird-McHale-Parish era; the 2004 Finals were the result of the Lakers being too old, too selfish, and too thrown together, a bunch of mercenaries as opposed to an integrated whole.

Yet, the larger point about pairs and trios in the NBA remains intact. We are still asking ourselves if this perimeter player and this big man — perhaps with this wing scorer or that stretch four — can win a title. Miami had a Big Three. So has San Antonio, despite the cultivation of a deep and valuable bench. (The Spurs’ Big Three was much more prominent during the years immediately following and preceding the Lakers’ two flourishes under Kobe Bryant.)

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Magic Johnson finished each other’s sentences in a way: Magic finished Kareem’s 1980 season, and Kareem helped Magic to overcome his personally disastrous 1984 Finals loss. Magic was the prime player Kareem needed in order to make the second half of his career a championship-laden success. Magic found out in 1990 and 1991 how much Kareem’s presence had meant to the Lakers.

Now, these two players — perfect complements to the other on so many levels, and perfect candidates to take the Laker franchise to places it had never been before, especially against the Celtics — can appreciate how much we’re still talking about great pairs and trios of NBA players, and what they can mean for a single organization.

Kareem and Magic. Magic and Kareem. They completed each other, they completed the Lakers, and they’ve completed so much of the story of professional basketball since the late 1960s.