Stephen Orr Spurrier is a figure who demands and deserves treatment on many levels: yes, as a football coach, but also as a personality, a professional in a rough business, an innovator, and as an architect of two programs. Had he stayed at Duke for several more years, Spurrier could have built three different schools into significant football forces before hanging up his whistle on Monday night.

In this piece, one new installment of our tribute to a seminal figure in the history of college football, we will focus solely on Spurrier’s impact on college football as a coach. More precisely, this piece is dedicated to Spurrier’s impact on the field, not his many memorable quotes or the lifestyle-based ways in which he offered a healthy example to the profession he leaves behind.

Very simply, Spurrier changed the way the game was played in the SEC. More than that, Spurrier’s approach to coaching — not as lifestyle, but solely in terms of gameday and its decisions — is something which can teach the sport of college football in the decades ahead. Spurrier, though no longer active as a coach, can influence the trajectory of the sport… if his former peers in the profession look deeply at what he meant to college football between the painted white lines.

*

Generations upon generations of football coaches built names, reputations, legacies, and championships on the tried-and-true foundations of defense, field position, the kicking game, and generally leveraging the 100-yard field against the opposition in a protracted struggle centered around brute strength and raw physical superiority at the line of scrimmage. Decade after decade, college football was a running back’s game. Archie Manning and Roger Staubach poked their heads into the fray and cut different paths in the sport, but those were occasional examples, exceptions to the larger flow and movement of the sport in the 20th century.

In the mid-1980s, Vince Dooley was still walking the sidelines at Georgia. Pat Dye was settling into his job at Auburn. Bill Curry, a Vince Lombardi-coached NFL player of distinction who wouldn’t retain Spurrier at Georgia Tech when he became the head coach of the Yellow Jackets in 1980, took over at Alabama in the latter half of the decade.

Bill Arnsparger, a legendary defensive coach with the Miami Dolphins, moved to LSU and made a Sugar Bowl in the middle of the 1980s. Johnny Majors was at Tennessee, and although he was willing to sling the ball around the yard at times in Knoxville, he won a national title with Tony Dorsett at Pittsburgh in 1976. He was no revolutionary in the college football ranks. Neither was Galen Hall, the coach at Florida for most of the 1980s.

Ole Miss, Mississippi State, Kentucky, Vanderbilt — these programs didn’t do a whole lot in the 1980s. Mississippi State enjoyed a moment of relative success in the early part of the decade under Emory Bellard, but little more. Kentucky made back-to-back bowls under Jerry Claiborne. Ole Miss began to gain some momentum under Billy Brewer at the very end of the decade, but that didn’t translate into top-tier success.

All in all, the 1980s marked an SEC decade in which there was Herschel Walker and Bo Jackson in the first half… and then a period of drift in the second half. Once two of the greatest running backs in college football history left for the NFL, the SEC didn’t know what to do with itself. No dominant team emerged. Teams in the state of Florida, the Miami Hurricanes and the Florida State Seminoles, forged the “it” rivalry in college football with a willingness to throw the ball. They regularly beat the challengers from Oklahoma and Nebraska, who hewed to the tried-and-true methods SEC coaches had cherished for generations.

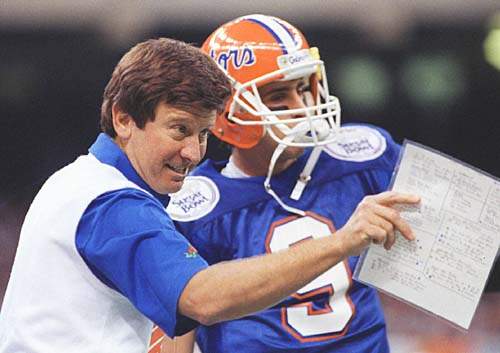

It was into this vacuum that Steve Spurrier stepped, after quietly building Duke into an ACC champion in three short seasons.

When Spurrier came to Florida, his alma mater, on the final day of the 1980s, little did college football know how much that decade — and all the decades which preceded it under men named Bryant and Neyland and Vaught and Dooley and Dye — would be left behind.

*

Here is the essential Steve Spurrier in strict football terms, contrasted against decades of The Bear and — beyond the SEC — the Woody Hayes-Bo Schembechler era in the Big Ten, not to mention the Tom Osborne-Barry Switzer clashes on the central plains of the Big Eight:

In an age when the kicking game was viewed as important, Spurrier — who was a punter for most of his NFL career with the San Francisco 49ers — loathed punts and field goals. He didn’t see the punt as a crucial instrument of leverage. He saw it for what it was: a failure.

Spurrier didn’t see field goals as incremental advantages in a defensive struggle; he saw them for what they were: insufficient.

While Woody and Bo and Tom and Barry and The Bear would pound the ball between the tackles, play after play, Spurrier would call a fade or a curl route play after play… until you showed you could stop it, of course. This totally redrew the boundaries of football, completely altering an understanding of the sport as it had come to be known by generations of Americans, both inside and outside the industry.

Spurrier, truly, was the foremost change agent in college football with respect to the sport we see today, a sport in which passing offenses and strategic fearlessness are much more common to what we watch on Saturdays.

This itself should be a lesson to the coaches Spurrier leaves behind, now that he’s no longer a peer, but a retired practitioner.

However, college football clearly has more to learn from Spurrier — not so much in the micro (throwing the ball more), but in the macro: namely, being willing to do things differently.

*

College football needs game-management assistant coaches, specialists who are paid only to make endgame decisions while the coach focuses on teaching his players how to play, or what plays to run.

College football programs need to understand line-of-scrimmage manipulation, meaning the act of running vigorously toward the line of scrimmage, only to make a handoff or stop-and-reversal, followed by a lateral, all in the service of a trick play which can get an easy touchdown. Advancements in this and other daring practices — things which are as foreign now as Spurrier’s methods were in the college football world of 1990 — are waiting to be exploited by a new visionary coach, but haven’t been pounced on yet.

Who will be the next Spurrier — not in terms of personality (that’s impossible), but in terms of new methods and new ways of seeing?

Hopefully, someone will step into the void, carrying Steve Spurrier and college football into a new century.