Earlier this week, we explored the various Final Four national semifinals (not championship games) that defined the product of college basketball on the court. This piece will look at Final Fours as a whole, not just the semifinal round. Moreover, it will also focus on off-court issues relating to race, economics, culture, and the length of a collegiate basketball player’s career. Which Final Fours mattered most in socioeconomic and cultural contexts?

10 – 1998 (WINNER: KENTUCKY)

Pat Forde of Yahoo! Sports has written a column on the declining presence of black coaches at the top tier of college basketball. The fact that a black head coach, Tubby Smith, was able to win a national championship at the program and school Adolph Rupp made famous should always serve as an indicator that anyone, anywhere, can succeed if skilled enough.

When he became the first black head coach to win the NCAA tournament in 1984 with Georgetown, John Thompson — as shown in the ESPN 30 for 30 film “Requiem For The Big East” — made it a point to pass over that distinction. Thompson told reporters that any attempt to play up the moment’s significance would suggest that a black coach had not been intelligent enough to win a basketball championship in previous decades. Thompson never did want to go down that road because of the logical extensions attached to a race-centric storyline in 1984.

Tubby Smith’s title might not have created as many Kevin Ollies as it should; however, that moment 16 years ago in San Antonio will always represent a symbolically potent occasion, one that — at any point in the future — might yet lead to more high-profile coaching jobs for African Americans.

9 – 2007 (WINNER: FLORIDA)

We live in an era in which the one-and-done player is becoming more commonplace in college basketball. More will be said on this subject as this list continues, but in 2007, a counterweight to the one-and-done movement emerged when NBA prospects Joakim Noah, Al Horford, and Corey Brewer all came back to school for another year; won a repeat national title; and did not suffer as professionals in the long run. Noah is enjoying an excellent career. Horford has been a highly productive player when not injured. Brewer, though not living up to the full measure of his potential, is still playing in the league and making enough contributions to the extent that his career is better than a bust. If there was ever an example from the past 10 years which points to collegiate seasoning and longevity as the better pre-NBA formula for a growing player, 2007 Florida provided it.

Should college players stay in school? That’s not what this example is meant to prove. Every player must decide what’s best for himself and his loved ones. This example is only meant to show that staying for another year can polish a player’s skill set and make him a better pro.

7 and 8, tie – 1971 (WINNER: UCLA) and 1982 (WINNER: NORTH CAROLINA)

When the subject of amateurism is discussed in college sports, it is always worth remembering that grownups with dollar signs in their eyes have been finding ways to make an extra buck for a very long time. The Final Four is played before 60, 70, or (this year in Jerry Jones’s pleasure palace) 80 thousand fans, and we’re used to such grand spectacles. Yet, the movement toward dome basketball — enabling the NCAA to sell that many more tickets for what is supposed to be a conventional-arena/gymnasium sport — is something that began almost 50 years ago.

The 1968 UCLA-Houston regular season game opened the door to all this, and younger fans of college basketball might not recall that the 1971 Final Four was played in the Astrodome. The Final Four’s dome model really didn’t catch on just then because the Astrodome — being the first major domed stadium built in the United States — just didn’t have the seating angles or portable bleachers to create a somewhat intimate basketball experience. However, when the Superdome staged the 1982 event — which happened to have quality games and an epic championship contest between Georgetown and North Carolina — the possibilities of dome basketball became evident. The success of 1982 is what led to the Final Fours we have today.

Plenty of money will be made on this Final Four. Kentucky’s one-and-dones will get their due compensation in the 2014 NBA Draft, and deservedly so. However, for Florida’s role players and the supporting casts on Wisconsin and Connecticut, where will be the fat paycheck down the line? A total of roughly 160,000 seats will be filled in two sessions on two separate days in the coming week. Many of these seats might as well be on the moon, given their (lack of) proximity to the floor in AT&T Stadium. Plainly put, a lot of people will spend a lot of money to fly to Dallas-Fort Worth; purchase memorabilia; party with fellow fans; and get a bad-view seat for the national semifinals (and the title game if their team wins on Saturday).

It sure seems as though these players are providing something very much under the umbrella of what one would refer to as entertainment.

Yes, there are tons of very thorny legal, structural and definitional issues related to what the Northwestern union movement is seeking to achieve. You might disagree — for good reasons — with the strategy of intending to form a union. That’s a very legitimate point, one worth discussing on a continuous basis.

Let the larger point stand, though: An expansive, mature conversation needs to happen, one that will wrestle with the larger structuring of collegiate athletics. Why? There are numerous and convincing reasons. The move to dome basketball, which began in Houston in 1968 and moved to the Final Four 43 years ago, is one of them.

What Kentucky did in 2012 has only given momentum to John Calipari’s one-and-done model, which was rescued the past two weeks by his 2014 Kentucky team.

6 – 2012 (WINNER: KENTUCKY)

Speaking of necessary conversations, one is occurring right now in relationship to the NBA’s rules for taking players out of college. The uneasy dance between college basketball and the NBA makes it important to give players the right balance between freedom and wise counsel, between empowerment and a sense of structure. Kentucky’s use of the one-and-done model under John Calipari has accelerated this conversation, and no recent Final Four put this topic squarely under the microscope more than the 2012 event, which launched Anthony Davis and Michael Kidd-Gilchrist to the pros after one season.

5 – 1973 (WINNER: UCLA)

This Final Four can also be filed in the “amateurism is a very hollow notion” folder. This was the Final Four in which the championship game moved from a weekend slot to its current Monday night home in prime time. The Final Four is a ticket-selling event, but it’s very much worth remembering that it is even more a television event. The 1973 Final Four marked a forward step in the programming of college basketball, just one more prime-time show among many.

4 – 2003 (WINNER: SYRACUSE)

Before there was Anthony Davis in a Final Four at the Superdome, Carmelo Anthony starred in a Final Four at the Superdome. What Melo achieved in 2003 represented the first truly prominent example of a one-and-done player owning the Final Four. Without Melo, would we have the conversations that are unfolding in the present day? Maybe… but perhaps not to the same extent.

3 – 1979 (WINNER: MICHIGAN STATE)

What Larry Bird and Magic Johnson achieved on that Monday night in Salt Lake City transformed the way college basketball was seen as a TV commodity. Without that game, the move to dome basketball and the other trends you’ve seen at the Final Four over the past 35 years might not have gotten off the ground; at the very least, they wouldn’t have emerged as quickly as they did. College basketball enjoys saturation coverage these days, and 1979’s Final Four is the one most responsible for that reality.

2 – 1963 (WINNER: LOYOLA OF CHICAGO)*

* = With a nod to the 1955 through 1960 Final Fours

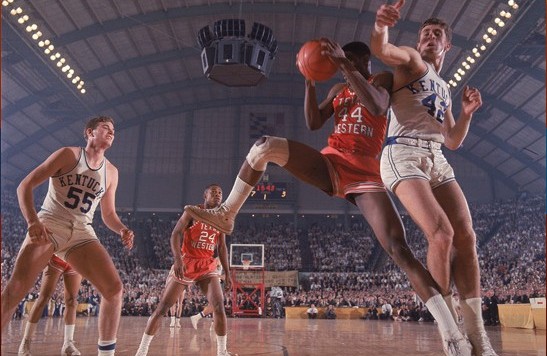

The nine-season period that began in 1955 and culminated in 1963 laid the groundwork for the culture’s larger acceptance of racially integrated college basketball. Bill Russell starred in the 1955 and ’56 Final Fours with San Francisco. Wilt Chamberlain owned the scene at the 1957 Final Four for Kansas. Elgin Baylor brought Seattle University to the big show in 1958. Oscar Robertson carried Cincinnati to the Final Four in 1959 and 1960. Then, in 1963, Loyola of Chicago and Cincinnati brought teams to the national title game that were mainly comprised of black starters, four for Loyola and three for Cincinnati. The Ramblers and Bearcats played one of the great college basketball games of all time in 1963’s final showdown; that certainly didn’t hurt. Nine years of excellence and prominence helped change the way basketball was seen and appreciated in this country. These nine years enabled one other Final Four to take its place in history.

1 – 1966 (WINNER: TEXAS WESTERN)

It wasn’t just that an all-black starting lineup won a national title; it was that said lineup beat a powerhouse program coached by a man whose views on race could not have been more hostile or oppositional. This fact — not just that Texas Western won, but that it smoked Adolph Rupp, of all people — enabled the 1966 Final Four to become the landscape-changing event that is still talked about today. When this Final Four’s 50th anniversary is celebrated in two years, we will all be reminded of the way in which one weekend in College Park, Md., changed an entire sport.